BUP Interview with Sumea Ramadani

Balkan University Press is happy to share the interview with Sumea Ramadani, the author of the forthcoming BUP publication "Two Worlds of Healing."

BUP: This book was born from your master’s thesis at International Balkan University. How did your experience as a master’s student there shape your research journey — both academically and personally — and what did you learn about transforming an academic study into a work that also speaks to the heart?

SR: First of all, yes, I learned immensely about how to transform an academic study into a work that also speaks to the heart. Writing research and writing a book are two entirely different experiences. In scientific work, you are guided by structure, precision, and rules that leave little space for personal expression. But writing a book invites something else, it asks for your authenticity, your originality, your emotions, and your voice. Through this process, I discovered how to bring together two worlds that often seem separate: science and literature. I learned how knowledge can coexist with feeling, and how the language of the mind can meet the language of the heart. My journey as a master’s student at the International Balkan University taught me not only how to think critically and write academically, but also how to breathe life and emotion into what I create.

BUP: Your book opens with a deeply personal reflection on writing as both expression and protection — even as a secret code only you could understand. How has writing evolved for you over time — from a coping mechanism into a professional and spiritual form of inquiry?

SR: Writing has always been my strongest form of catharsis. It remains a coping mechanism perhaps that is precisely why I chose academia as my path: to continuously explore myself through reading and writing, and through writing, to return again to reading. In that rhythm, I find both self-discovery and distance. The ability to observe my own emotions and thoughts with a kind of gentle objectivity, as if I were both the subject and the observer of my own life. Writing allows me to translate the intangible feelings, memories, and fragments of thought into something I can understand, something that speaks back to me.

In psychotherapy and psychology, we often say that life is not only about living, but also about creating a story out of the life we live. Writing, for me, is that act of creation, the transformation of experience into meaning, the moment when pain begins to form language and becomes art. It is where reflection replaces reaction, where chaos begins to find coherence. It has evolved over time, yet in many ways, it remains as raw and instinctive as it once was born from the same need to make sense of the world within and around me. Today, I see writing as an aesthetic form of existence, a way of perceiving, tasting, and inhabiting life more fully, with awareness and grace. It is both a mirror and a window. A mirror that reveals the truth of who I am, and a window that opens to everything I still wish to understand.

BUP: You describe your journey into the topic of addiction as a pilgrimage into the human condition. What moment during your fieldwork most changed your understanding of human suffering or healing?

SR: When I first entered the monastery and later the psychiatric hospital, when I met people struggling with addiction, the patients and the protégés. I realized something that deeply changed me. I never saw monsters in them, as society so often does. I saw frightened children, trying to cope with a world that felt too heavy to bear. They were not running toward drugs; they were running away from pain. They were seeking a way to control what felt uncontrollable, to manipulate the brain just enough to make existence feel a little safer. But I learned that you can never truly manipulate the brain, you can only harm it in that way. That realization shifted my entire perception of human nature. I began to see more clearly that we are profoundly social beings, we depend on each other not only to survive, but to make life gentler, more bearable. Life itself is already complex and demanding; our task as human beings should be to ease each other’s burdens, not to multiply them. This work, this research, changed me not only as a professional, but as a person. It made me a better human being. Throughout this journey, I met extraordinary individuals, people who have sacrificed everything to help others heal, people who have remained deeply human even after witnessing misery, dysfunction, and systemic failure. Their quiet strength, compassion, and persistence reminded me that healing is not only a psychological or spiritual act, it is also a profoundly moral one. After witnessing and experiencing this process, I can say with certainty that I am richer not in knowledge alone, but in humanity.

BUP: Your study moves fluidly between psychiatric hospitals and a monastery — between scientific interviews and sacred rituals. How did you navigate these two worlds methodologically and emotionally, and what did you discover at their intersection?

SR: I have to admit that navigating these two worlds, the psychiatric hospital and the monastery was one of the most challenging parts of my research, both methodologically and emotionally. On one side stood the conventional: structured teams of psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, clear protocols, measurable outcomes, assessments that could indicate whether a person was ready to return to the world. On the other side was the unconventional: the monastery, where healing unfolded in silence, prayer, ritual, and human connection where progress was not measured by tests but by the quiet permission and blessing of the priest, by a sense of inner peace that could not be quantified. Comparing these two approaches was never easy. Science seeks evidence, while faith seeks meaning yet, within me, they somehow began to coexist. I realized that both systems, though different in language and method are ultimately trying to touch the same human wound, the longing to be understood, to be accepted, to be free from pain. It was difficult to measure the “success” of the monastery’s approach in scientific terms, but emotionally, something within me knew that healing was taking place. If something works, if it eases suffering, if it restores dignity then it deserves to be seen, studied, and written into the broader landscape of science. As I wrote in the book and my thesis: if you don’t know exactly what to do when facing human suffering, just do something. Compassion, even without a perfect method, can still be profoundly healing. That is the greatest lesson I took from this comparative journey between medicine and faith, between structure and spirit.

BUP: You mention that your topic faced skepticism from the academic world for being “unconventional.” Looking back, what gave you the conviction to pursue it anyway, and what advice would you offer to young researchers who wish to follow intuition over convention?

SR: My topic did face skepticism from the scientists. It was seen as unconventional, perhaps even too spiritual or abstract to fit neatly into academic frameworks. But I think that is exactly what gave me the conviction to pursue it. I’ve always believed that research should not only confirm what we already know but also dare to explore what we don’t yet understand. If something in you feels true if it calls you to question, to wonder, to connect different worlds then that is worth following. What sustained me was persistence and curiosity. Persistence, because every meaningful idea requires the courage to stand alone before it is accepted. And curiosity, because it keeps the mind open and the heart humble it reminds you that knowledge is not only found in data, but also in people, in silence, in experience. To young researchers, I would say: don’t be afraid to follow your intuition, even when it leads you beyond convention. Academia needs new questions as much as it needs new answers. Be rigorous, but also brave. Science evolves through those who dare to see differently.

BUP: You write that addiction “isn’t just a clinical disorder — it’s a mirror.” If you were to summarize what that mirror reflected about society in North Macedonia, what would it show us about our collective wounds, silences, and capacity for transformation?

SR: If addiction is a mirror, then in North Macedonia it reflects not only the pain of the individual, but the fractures of an entire society. It reveals how loneliness has become one of our deepest collective wounds, how silence has replaced dialogue and how judgment too often stands where understanding should be. Behind every person struggling with addiction, there is a story of disconnection: from family, from community, from purpose… It is not merely the failure of one individual’s will, but often the failure of a system to nurture belonging. This mirror shows us how our society tends to heal through suppression rather than expression. We hide pain, we moralize suffering, we fear vulnerability. And yet, within this same reflection, I also see our potential for transformation. Because where there is pain, there is also the possibility of awakening. Addiction, in this sense, exposes the truth we prefer not to face: that healing cannot come from punishment or exclusion, but from empathy, dialogue, and the courage to rebuild human connection.

If we dare to look closely into that mirror, not to condemn, but to understand we may find that what we call addiction is, in fact, the human cry for meaning in a world that too often forgets the soul.

Sumea Ramadani is a Psychological Counselor, Clinical Psychologist, and PhD candidate in Andragogy at the Institute of Pedagogy, Faculty of Philosophy, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje and the Psychology Faculty of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at International Balkan University. She is a Teaching Assistant at the International Balkan University (IBU), Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, where she lectures in psychology and psychotherapy. Guided by the belief that “healing is not the end of the story but the beginning of a new one,” Sumea integrates scientific, cultural, and philosophical perspectives in this book about different worlds of healing.

Latest News

-

Opened call for the new issue of TEFMJ

Date: 10.02.2024 -

The Journal of Law and Politics welcomes your papers

Date: 10.02.2024 -

-

Call for Papers for an Edited Volume

Date: 27.05.2024 -

Open Call for Chapter Proposals

Date: 27.05.2024 -

The new issue of Journal of Law and Politics is here!

Date: 01.05.2024 -

TEFMJ June issue is published

Date: 01.07.2024 -

IJEP's Vol. 5, Issue 1 is now available!

Date: 02.07.2024 -

Vol. 4, Issue 1 - IJTNS

Date: 01.07.2024 -

The first IJAD volume is online!

Date: 02.07.2024 -

Balkan University Press Launches the Journal of Balkan Architecture

Date: 15.07.2024 -

-

Balkan Political Economy Series welcomes your proposals

Date: 18.07.2024 -

BUP Interview with Prof. Marija Miloshevska Janakieska

Date: 18.07.2024 -

BUP Interview with Asst. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Lökçe

Date: 24.07.2024 -

-

Prof. Xhaferi's blog for BUP

Date: 28.08.2024 -

-

-

IJEP is now indexed in the Copernicus Journals Master List

Date: 23.09.2024 -

BUP INTERVIEW WITH PROF. ISMAIL GÜLEÇ AND ASST. PROF. MÜMIN ALI

Date: 26.09.2024 -

BUP Interview with Prof. Dzemil Bektovic

Date: 04.10.2024 -

-

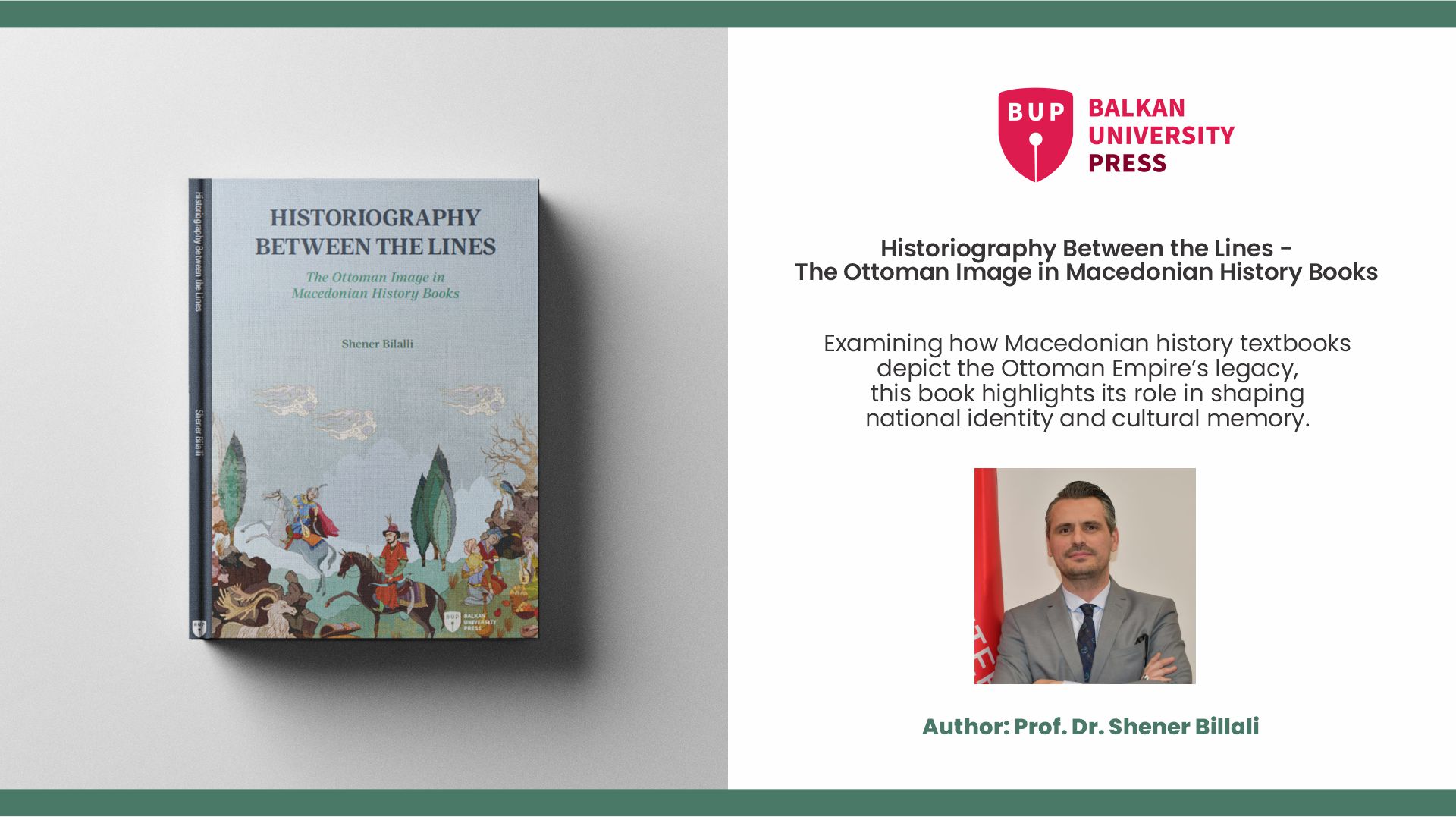

BUP Interview with Prof. Shener Bilalli

Date: 30.10.2024 -

BUP Academic Blog with Prof. Tamás Szemlér

Date: 08.11.2024 -

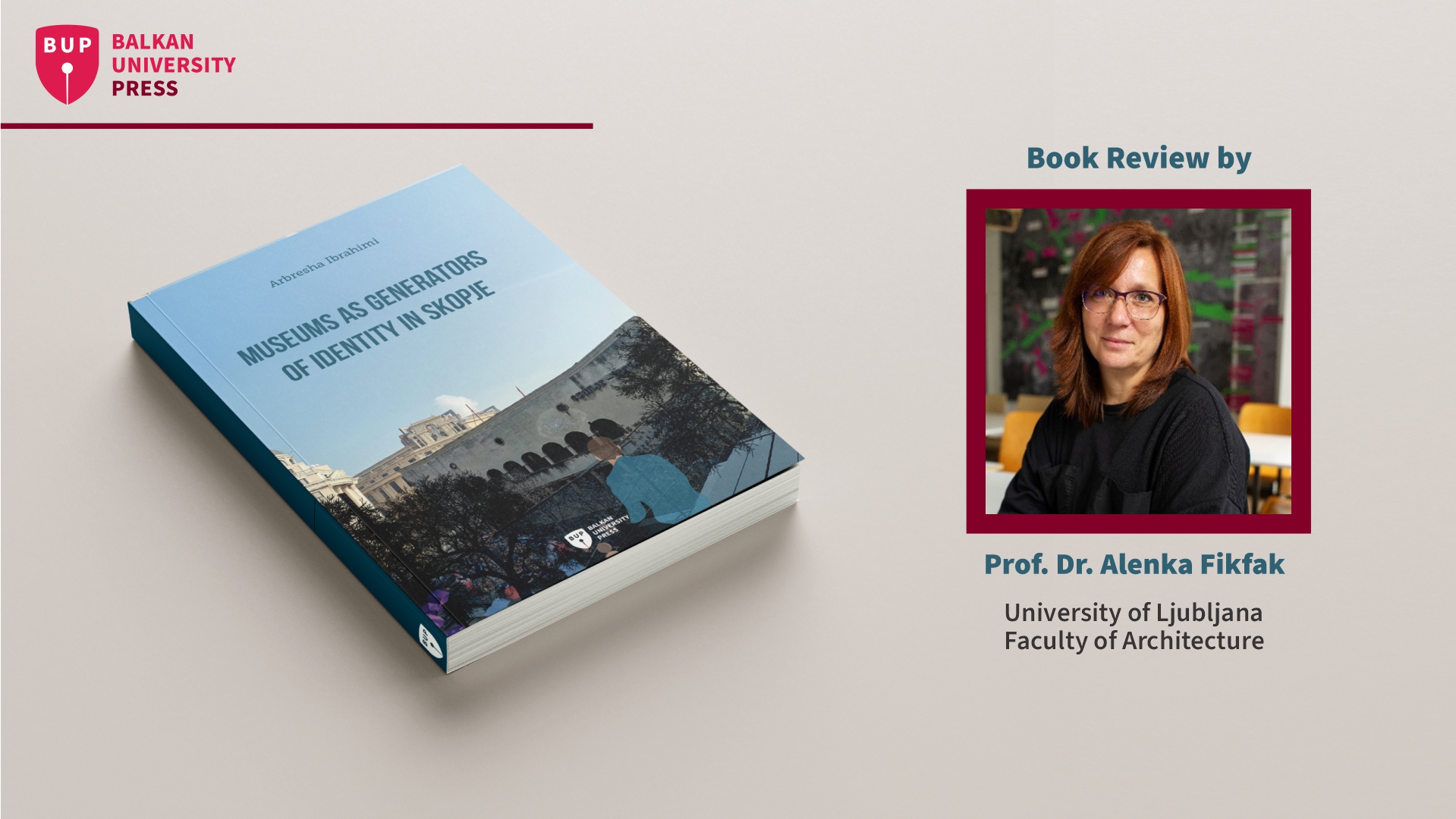

Book Review for "Museums as Generators of Identity in Skopje"

Date: 20.11.2024 -

BUP Interview with Arbresha Ibrahimi

Date: 25.11.2024 -

The first volume of Balkan Research Journal is here

Date: 02.12.2024 -

Volume 5, Issue 2 of the Journal of Law and Politics is published

Date: 31.10.2024 -

The inaugural issue of Journal of Balkan Architecture is published

Date: 29.11.2024 -

BUP Launch Event

Date: 10.12.2024 -

Grand Launch of Balkan University Press

Date: 12.12.2024 -

BALKAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Date: 09.01.2025 -

Publication of a book

Date: 30.12.2024 -

Publication of a book

Date: 24.12.2024 -

The December Issue of IJEP is published

Date: 31.12.2024 -

The December Issue of TEFMJ is published

Date: 16.01.2025 -

-

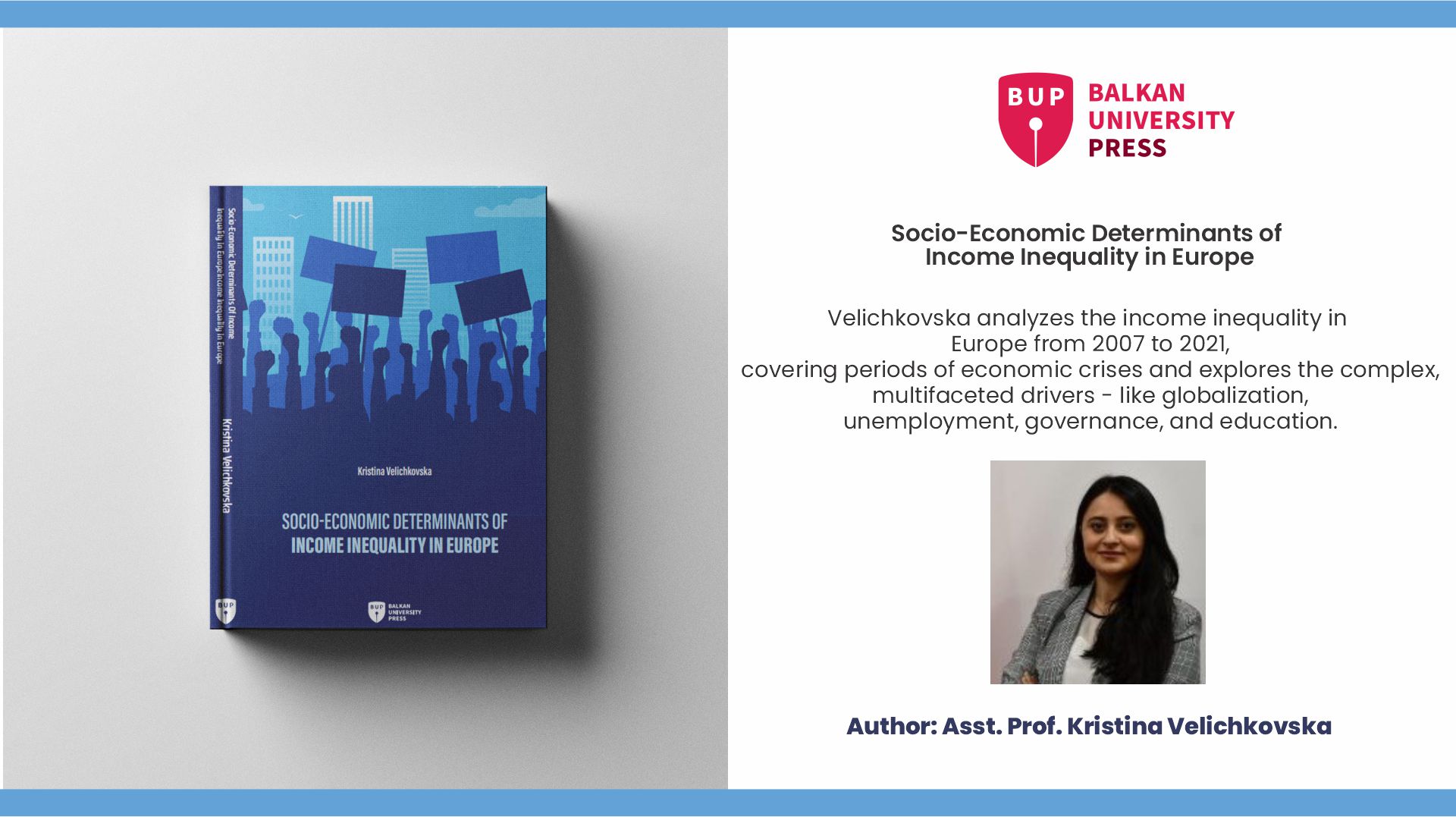

BUP Interview with Asst. Prof. Kristina Velichkovska

Date: 29.01.2025 -

-

-

BUP Interview with Kefajet Edip

Date: 18.02.2025 -

BUP Academic Blog by Frank Weinreich

Date: 20.02.2025 -

-

-

BUP Interview with Prof. Dr. Ana Kechan

Date: 30.04.2025 -

BUP Interview with Ozlem Kurt

Date: 14.05.2025 -

BUP Interview With Assoc. Prof. Igballe Miftari-Fetishi

Date: 03.09.2025 -

Publication of the book "An Integrated Approach to Academic Reading"

Date: 09.09.2025 -

BUP Interview with Nikola Dacev

Date: 15.09.2025 -

Publication of the book "Civil Law"

Date: 17.09.2025 -

BUP Interview with Ekaterina Namicheva Todorovska

Date: 22.09.2025 -

.png)

-

The first book of the Balkan Political Economy Series is published

Date: 07.10.2025 -

OPEN CALL for Book Chapters

Date: 08.10.2025 -

-

.png)

-

.png)

Publication of the book "Two Worlds of Healing" by Sumea Ramadani

Date: 05.11.2025 -

New BUP Publication

Date: 23.12.2025 -

Publication of the book "Kuzey Makedonya Kitabeleri"

Date: 26.12.2025