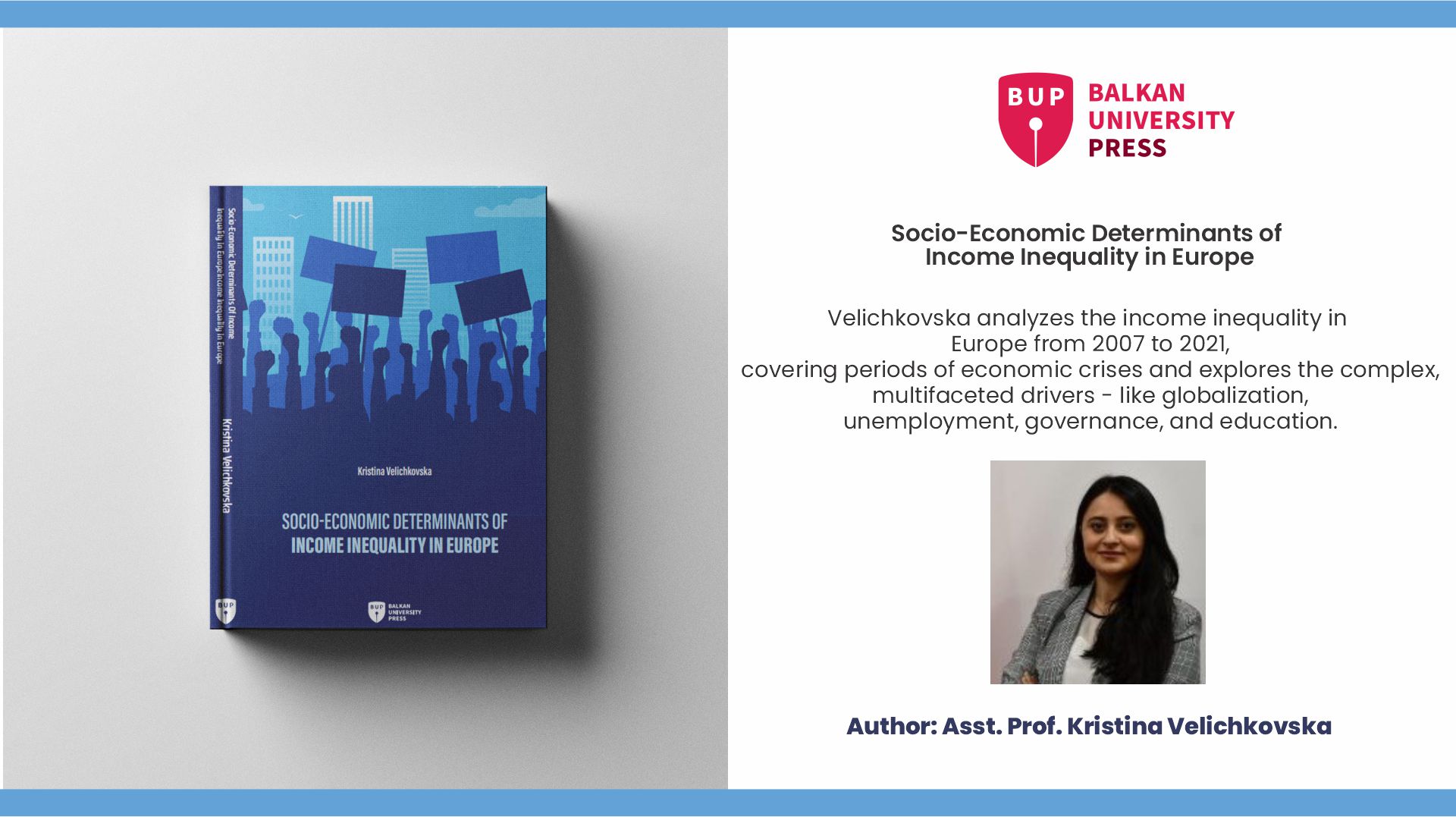

BUP Interview with Asst. Prof. Kristina Velichkovska

Balkan University Press is excited to share an interview with Asst. Prof. Kristina Velichkovska, following the publication of her book "Socio-Economic Determinants of Income Inequality of Europe" published by BUP.

Could you tell us more about yourself and your motivation to research the topic of European income inequality? How does this relate to the income inequality in the Balkans?

I’m a researcher who’s curious about the “why” behind important issues, especially when it comes to things that really matter. Income inequality is one of those issues that hits close to home because it’s not just about numbers—it’s about opportunities, well-being, and fairness. Europe is such a diverse continent, with countries at different stages of economic development, so it felt like the perfect setting to explore how inequality evolves and what we can learn from it. The Balkans, where I’m from, add another layer to this complexity, as the region has its own unique challenges tied to its history, governance, and ongoing economic transitions. Connecting these dots was both a personal and intellectual journey for me.

I wanted to understand what drives income inequality more in developing countries compared to the developed European countries. This would allow us to create targeted policies tailored to each country’s unique context, rather than simply copying solutions that may not be effective everywhere. Another area I focus on is how different types of crises we’ve experienced in the last two decades—whether financial, public health, or others—have affected income inequality. Understanding these dynamics helps us prepare better for future crises and respond in ways that minimize inequality instead of deepening it.

How did you find European income inequality varied across different crises, such as the global financial crisis, the sovereign debt crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic?

What’s really interesting is how each crisis highlighted different aspects of inequality. During the global financial crisis, it was all about job losses, especially for low-income workers, and the domino effect that had on families and communities. The key factors driving inequality then were things like GDP per capita, unemployment, investments, education levels, and political issues like corruption and rule of law. The sovereign debt crisis hit southern Europe particularly hard, showing inequalities not just between countries, but within them as well. In this case, GDP per capita, unemployment, education levels, and political stability were the main factors at play. Then came COVID-19, which really magnified existing inequalities. It didn’t just expose gaps—it made them worse. Things like healthcare access, the ability to work from home, and digital education became huge factors in who could cope with the crisis and who couldn’t. But the big standout during COVID-19 was the role of education. It was the one factor that really drove income inequality during the pandemic.

What struck me across all these crises is that the only constant factor influencing income inequality was the level of education. This really drives home how critical education is in either easing or widening inequality. Whether it’s a financial crisis, a public health crisis, or something else, education is key, and that’s why it should be a major focus for policymakers moving forward.

Your findings highlight economic globalization as a consistent factor in reducing European income inequality. Could you elaborate on how deeper economic integration contributes to a fairer wealth distribution, especially during economic disruption?

Economic globalization can be a double-edged sword, but when it’s done right, it levels the playing field. Trade and foreign investment create jobs and opportunities that might not exist otherwise, especially in less-developed regions. When countries integrate economically, they benefit from shared markets and resources, which can boost productivity and incomes. During economic disruptions, however, the benefits of globalization depend on how resilient the systems are. For example, in countries with strong institutions and safety nets, globalization can help stabilize economies by keeping trade flows open and maintaining investor confidence. But in countries without those safeguards, the same forces can widen gaps instead of closing them. It’s a reminder that while globalization has the potential to reduce inequality, it’s not automatic—it needs the right policies and governance to ensure its benefits are distributed fairly.

The book discusses how unemployment impacts income inequality differently during crises and stable periods. Can you explain why unemployment increases inequality during economic shocks but seems to reduce it in more stable times?

This is one of those paradoxes that really intrigued me during my research. During crises, unemployment hits the most vulnerable groups first—low-income workers, part-time employees, and those in precarious jobs. These groups don’t just lose income; they lose stability, which widens inequality almost immediately. But in stable periods, unemployment can sometimes have the opposite effect. When economies grow and unemployment falls, the new jobs created often go to those at the bottom of the income ladder. It’s like giving people a second chance to catch up. It’s all about the context and the strength of the social systems in place.

You confirm the Kuznets hypothesis with a European context in your study, noting an inverted U-shaped relationship between income inequality and economic development. Given this finding, what implications do you see for policies in developing versus developed European countries aiming to reduce inequality?

The Kuznets hypothesis is like a roadmap for inequality—it shows us that inequality often rises during the early stages of economic development and then falls as economies mature. For developing European countries, this means prioritizing investments in education, healthcare, and infrastructure to ensure that growth benefits everyone. For developed countries, the focus should shift to fine-tuning—things like progressive taxation, inclusive labor policies, and tackling residual inequality in sectors that haven’t caught up. The key takeaway is that no matter where a country is on the curve, there’s always work to do to make growth more inclusive.

On another note, you are the first PhD awarded by the Faculty of Economic and Administrative Sciences at IBU. Do you consider yourself an IBU success story, and what advice can you give to your students as future economists?

Honestly, I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunities I did at IBU. The university provided me with a strong academic foundation and the opportunity to excel in research and teaching. I am grateful for the supportive environment that helped me achieve milestones such as graduating summa cum laude and contributing to meaningful research.

If I have any advice for my students, it’s this: Always ask “why.” Don’t be afraid to challenge assumptions or dig deeper into the issues that matter to you. The world doesn’t need more economists who stick to the script; it needs thinkers who are willing to question, innovate, and create change.

And most importantly, remember that economics isn’t just about numbers—it’s about people. Never lose sight of that.

Kristina Velichkovska is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, International Balkan University, Skopje. She holds a PhD in Economics and is a graduated economist with a master's degree in Business Administration. Her areas of interest are macroeconomics, income inequality, and corporate finance. She has authored and co-authored several scientific papers in the field of economics and organizational sciences and is the author of the book "Socio-Economic Determinants of Income Inequality in Europe" published by Balkan University Press.

Latest News

-

Opened call for the new issue of TEFMJ

Date: 10.02.2024 -

The Journal of Law and Politics welcomes your papers

Date: 10.02.2024 -

-

Call for Papers for an Edited Volume

Date: 27.05.2024 -

Open Call for Chapter Proposals

Date: 27.05.2024 -

The new issue of Journal of Law and Politics is here!

Date: 01.05.2024 -

TEFMJ June issue is published

Date: 01.07.2024 -

IJEP's Vol. 5, Issue 1 is now available!

Date: 02.07.2024 -

Vol. 4, Issue 1 - IJTNS

Date: 01.07.2024 -

The first IJAD volume is online!

Date: 02.07.2024 -

Balkan University Press Launches the Journal of Balkan Architecture

Date: 15.07.2024 -

-

Balkan Political Economy Series welcomes your proposals

Date: 18.07.2024 -

BUP Interview with Prof. Marija Miloshevska Janakieska

Date: 18.07.2024 -

BUP Interview with Asst. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Lökçe

Date: 24.07.2024 -

-

Prof. Xhaferi's blog for BUP

Date: 28.08.2024 -

-

-

IJEP is now indexed in the Copernicus Journals Master List

Date: 23.09.2024 -

BUP INTERVIEW WITH PROF. ISMAIL GÜLEÇ AND ASST. PROF. MÜMIN ALI

Date: 26.09.2024 -

BUP Interview with Prof. Dzemil Bektovic

Date: 04.10.2024 -

-

BUP Interview with Prof. Shener Bilalli

Date: 30.10.2024 -

BUP Academic Blog with Prof. Tamás Szemlér

Date: 08.11.2024 -

Book Review for "Museums as Generators of Identity in Skopje"

Date: 20.11.2024 -

BUP Interview with Arbresha Ibrahimi

Date: 25.11.2024 -

The first volume of Balkan Research Journal is here

Date: 02.12.2024 -

Volume 5, Issue 2 of the Journal of Law and Politics is published

Date: 31.10.2024 -

The inaugural issue of Journal of Balkan Architecture is published

Date: 29.11.2024 -

BUP Launch Event

Date: 10.12.2024 -

Grand Launch of Balkan University Press

Date: 12.12.2024 -

BALKAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Date: 09.01.2025 -

Publication of a book

Date: 30.12.2024 -

Publication of a book

Date: 24.12.2024 -

The December Issue of IJEP is published

Date: 31.12.2024 -

The December Issue of TEFMJ is published

Date: 16.01.2025 -

-

-

-

BUP Interview with Kefajet Edip

Date: 18.02.2025 -

BUP Academic Blog by Frank Weinreich

Date: 20.02.2025 -

-

-

BUP Interview with Prof. Dr. Ana Kechan

Date: 30.04.2025 -

BUP Interview with Ozlem Kurt

Date: 14.05.2025 -

BUP Interview With Assoc. Prof. Igballe Miftari-Fetishi

Date: 03.09.2025 -

Publication of the book "An Integrated Approach to Academic Reading"

Date: 09.09.2025 -

BUP Interview with Nikola Dacev

Date: 15.09.2025 -

Publication of the book "Civil Law"

Date: 17.09.2025 -

BUP Interview with Ekaterina Namicheva Todorovska

Date: 22.09.2025 -

.png)

-

The first book of the Balkan Political Economy Series is published

Date: 07.10.2025 -

OPEN CALL for Book Chapters

Date: 08.10.2025 -

-

.png)

-

BUP Interview with Sumea Ramadani

Date: 24.10.2025 -

.png)

Publication of the book "Two Worlds of Healing" by Sumea Ramadani

Date: 05.11.2025 -

New BUP Publication

Date: 23.12.2025 -

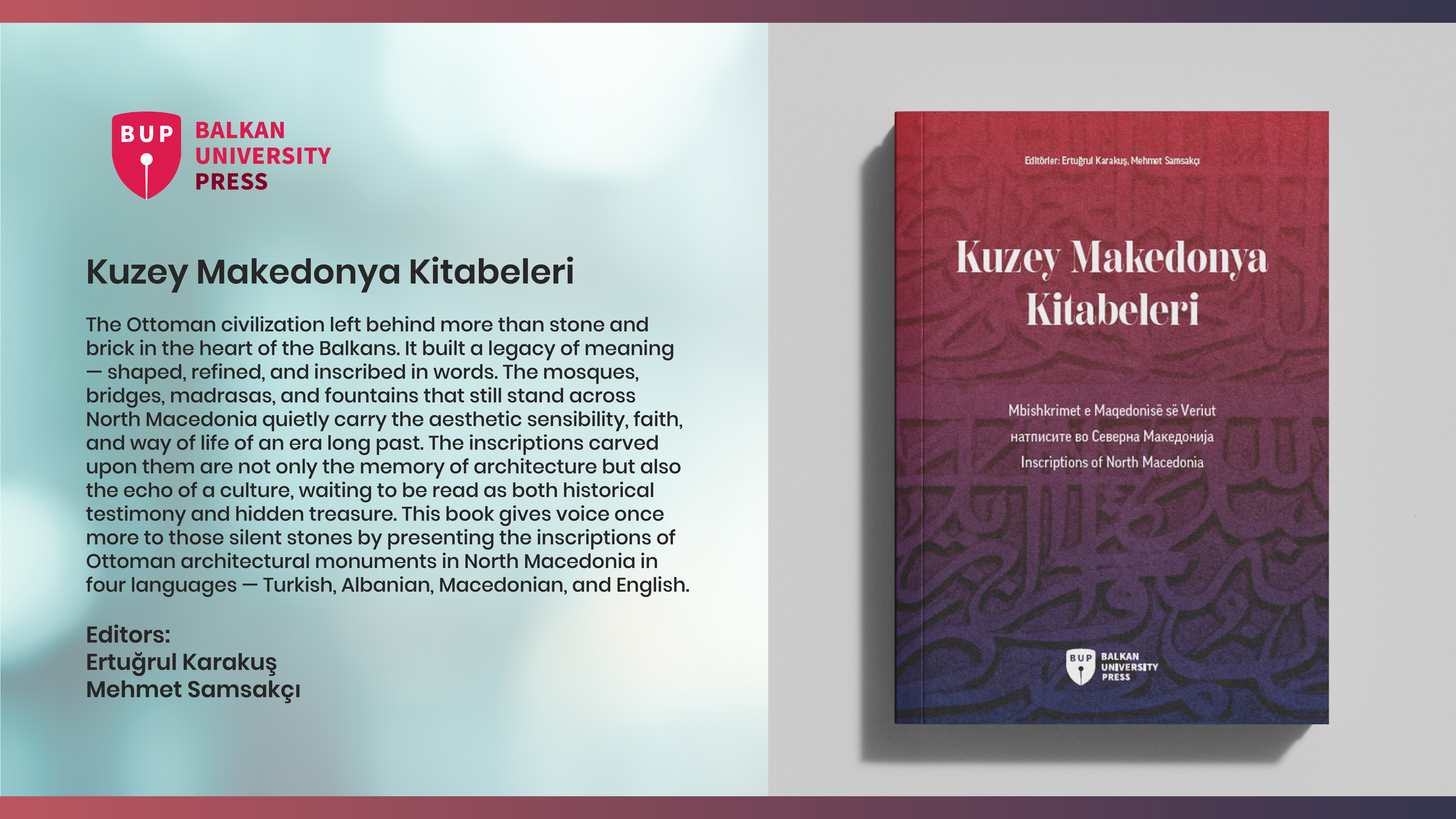

Publication of the book "Kuzey Makedonya Kitabeleri"

Date: 26.12.2025