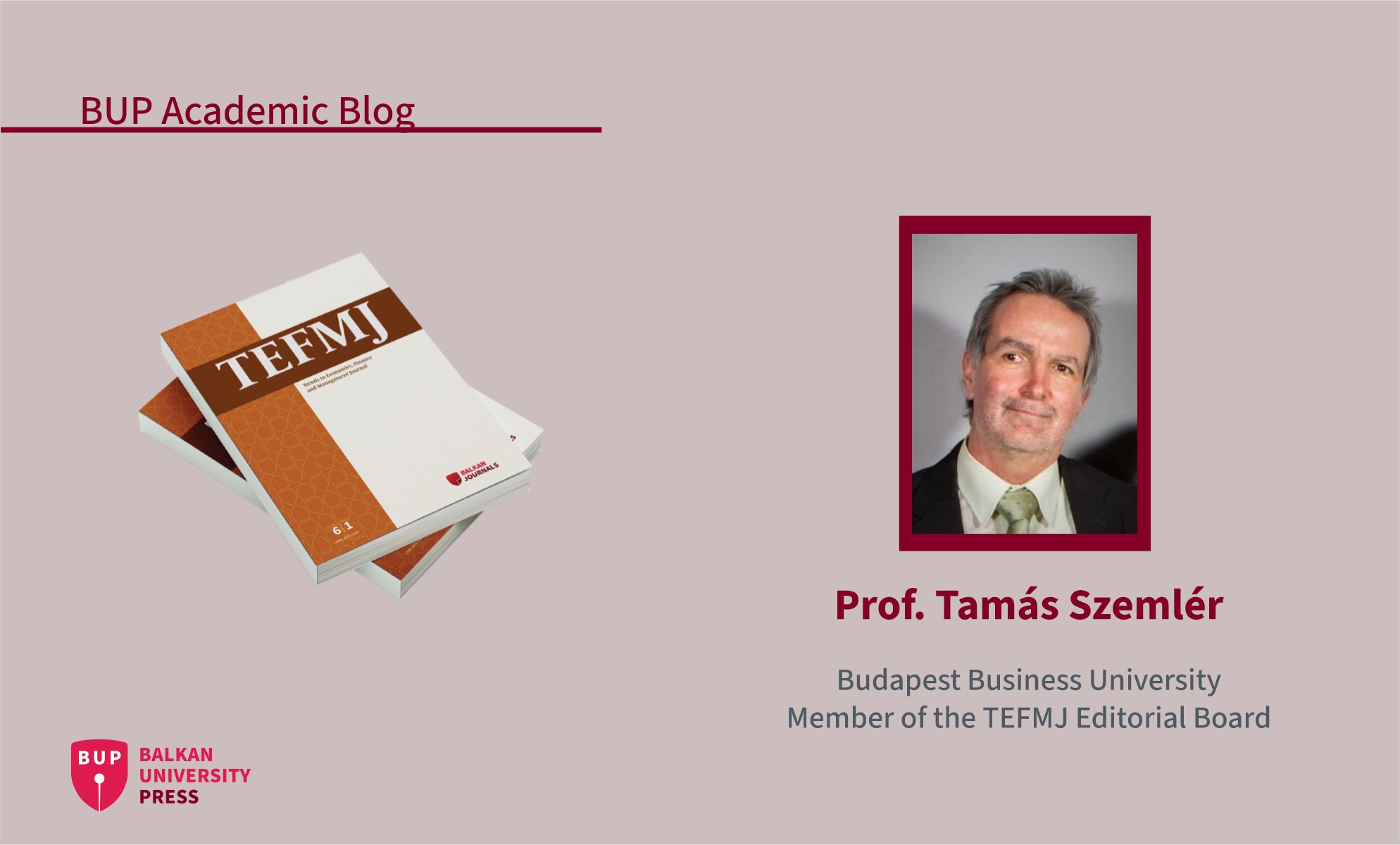

BUP Academic Blog with Prof. Tamás Szemlér

Handling Complex Issues in Teaching Economics at Universities

In this contribution, I address some important issues in the teaching of complex problems in economics at universities. Due to their complexity, however, these problems are far from being purely economic.

I address the well-known, still difficult questions (What should we teach? How deeply and/or (!) how clearly can we convey the knowledge? How to teach – e.g., the relationship between models and practice? How do we measure the success of education? etc.) that have become even more complex by recent dramatic changes in the world. As a result, the answers that can and even should be given have also changed – this is what I discuss here briefly.

Complexity is a well-known phenomenon. It is present everywhere; in teaching/researching economics, it raises questions related to basic economics, advanced economics, policy-oriented and academic research. Obviously, the complexity of all these aspects – as well as the complexity of the content within each of them – must be properly tackled. It is not an easy task.

An interdisciplinary approach is of crucial importance. Various fields of economics include many „components” from other disciplines. The tools economists use stem from mathematics, statistics, but also (and increasingly) from psychology and other sciences. Despite recent increases in their importance, their presence is still limited in many curricula.

The reasons for their underrepresentation are familiar for those who teach economics at universities: as in many other fields, there is increasing demand for „simple solutions”. The main reasons for this are time constraint, limited preliminary knowledge of the audience, and, in many cases, the lack of interest in digging deeper.

The question is how to deal with these obstacles. Simplification is one of the potential responses, but it works differently in different cases: teaching economics for economists and for non-economists raises different issues, therefore different paths are possible (even necessary).

In the first case, a solid and (at least) in some respects deep knowledge is necessary, while the second case is about providing useful knowledge for non-specialists. The two cases also differ from each other in what we can build upon. The question whether the (prior) knowledge necessary is there at the students’ side is crucial. And, in practice, the replies may vary case by case.

Flexibility in defining building blocks of knowledge (to give more information on a given topic for those who will need it for their future work, and less for those for whom the information related to that topic can be considered as less important). This requires a systemic approach, careful planning and a high degree of adaptation.

Even if all that is available, prior knowledge of the students remains a crucial factor. Specific forms of the appearance of this are the tasks to deal with students entering MA programmes with various former BA studies and with students entering PhD programmes with various MA studies.

Regarding research in economics, academic and policy-oriented research are often distinguished. Linkages between them are necessary (on the long run, no quality policy-oriented research is possible without solid foundations). Research results can constitute a valuable input for education; their presentation can differ according to specific objectives and target groups. Last, but not least, long-term orientation is crucial – even if it is very difficult to defend in today’s world full of rapid changes.

There are two key messages that can help the practical approach to the issues raised here. The first one is that communication is crucial. It is highly important to avoid seemingly simple solutions – oversimplification is not a good solution (even if it can look attractive from some angles). One should always underline the objectives of the topic (e.g., what is a simple model good for?) and show the limits as well as refer to connections to other approaches and disciplines. It is also essential to communicate the content (and it is also true for research outcomes) in an understandable way – otherwise even the most valuable messages have little chance to reach the minds of our target groups.

The second key message is that we need to systemise and make our education plans (programmes, curricula) flexible as much as possible. Solid, long-term frameworks (structures, rules, etc.) can help in designing a systemic approach – unfortunately, we do not always have them at our disposal. Well prepared, coordinated, systemic changes can also help – but „change for itself” does not necessarily do so. Finally, built-in flexibility of the system is of key importance.

Dr. Tamás Szemlér PhD, Head of Institute, Associate Professor (habil.), Budapest Business University, Faculty of Commerce, Hospitality and Tourism, Institute of Economics, Department of Economics and Business Studies. He is an economist and an educator with a demonstrated history of working in research and higher education. His teaching and research experience is in topics related to Macroeconomics, Economic Policy, International Relations, European Studies, World Economics. Assoc. Prof. Szemlér speaks seven languages: Hungarian (mother tongue), English, French, German, Italian, Russian, Bulgarian. He is a member of the TEFMJ editorial board.

.png)

.png)

.png)